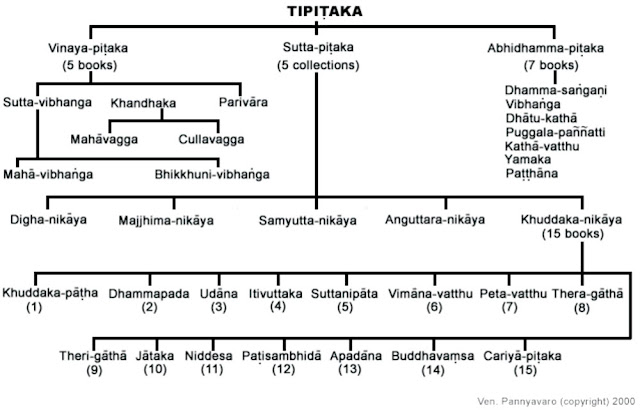

There are totally 62 volumes of the Buddhist Canon.

2:24:2:21. Mindfulness is the way to the Deathless (Nibb3na),' unmindfulness is the way to Death. Those who are mindful do not die; those who are not mindful are as if already dead.

===========================

Myanmar Tipitaka Books List

===========================

//Total 62 Books//

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

::Myanmar Vinaya Pitaka Books::

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

01. Myanmar Tipitaka – Vinaya Pitaka – Parajikapali

02. A. Myanmar Tipitaka – Vinaya Pitaka – Pacittiyapali-Bhikkhu

02. B. Myanmar Tipitaka – Vinaya Pitaka – Pacittiyapali-Bhikkhuni

03. Myanmar Tipitaka – Vinaya Pitaka – Mahavaggapali

04. Myanmar Tipitaka – Vinaya Pitaka – Cullavaggapali

05. Myanmar Tipitaka – Vinaya Pitaka – Parivarapali

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

::Myanmar Sutta Pitaka Books::

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

06. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Digha Nikaya – Silakkhandavagga

07. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Digha Nikaya – Mahavagga

08. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Digha Nikaya – Pathikavagga

09. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Majjhima Nikaya – Mulapannasa

10. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Majjhima Nikaya – Majjhimapannaasa

11. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Majjhima Nikaya – Uparipannaasa

12. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Samyutta Nikaya – Sagathavaggo

13. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Samyutta Nikaya – Nidanavaggo

14. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Samyutta Nikaya – Khandavaggo

15. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Samyutta Nikaya – Salayatanavaggo

16. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Samyutta Nikaya – Mahavaggo

17. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Anguttara Nikaya – Ekakanipata

18. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Anguttara Nikaya – Dukanipata

19. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Anguttara Nikaya – Tikanipata

20. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Anguttara Nikaya – Catukkanipata

21. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Anguttara Nikaya – Pancakkanipata

22. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Anguttara Nikaya – Chakkanipata

23. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Anguttara Nikaya – Sattakanipata

24. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Anguttara Nikaya – Athtakanipata

25. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Anguttara Nikaya – Navakanipata

26. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Anguttara Nikaya – Dasakanipata

27. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Anguttara Nikaya – Ekadasakanipata

28. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Khuddaka Nikaya – Khuddakapaat

29. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Khuddaka Nikaya – Dhammapada

30. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Khuddaka Nikaya – Udana

31. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Khuddaka Nikaya – Itivuttaka

32. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Khuddaka Nikaya – Suttanipata

33. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Khuddaka Nikaya – Vimanabatthu

34. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Khuddaka Nikaya – Petabatthu

35. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Khuddaka Nikaya – Patisambhidamagga

36. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Khuddaka Nikaya – Therapadana

37. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Khuddaka Nikaya – Theripadana

38. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Khuddaka Nikaya – Buddhavamgsa

39. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Khuddaka Nikaya – Cariyapitaka

40. Myanmar Tipitaka – Sutta Pitaka – Khuddaka Nikaya – Milindapanha

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

::Myanmar Abhidhamma Pitaka Books::

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

41. Myanmar Tipitaka – Abhidhamma Pitaka – Dhammasangani

42. Myanmar Tipitaka – Abhidhamma Pitaka – Vibhanga-1 – Khandavibhanga

43. Myanmar Tipitaka – Abhidhamma Pitaka – Vibhanga-2 – Ayatanavibhanga

44. Myanmar Tipitaka – Abhidhamma Pitaka – Vibhanga-3 – Dhatuvibhanga

45. Myanmar Tipitaka – Abhidhamma Pitaka – Vibhanga-4 – Saccavibhanga

46. Myanmar Tipitaka – Abhidhamma Pitaka – Vibhanga-5 – Indriyavibhanga

47. Myanmar Tipitaka – Abhidhamma Pitaka – Vibhanga-6 – Paticcasamuppada

48. Myanmar Tipitaka – Abhidhamma Pitaka – Vibhanga-7 – Satipatthanavibhanga

49. Myanmar Tipitaka – Abhidhamma Pitaka – Vibhanga-8 – Sammappadhanavibhanga

50. Myanmar Tipitaka – Abhidhamma Pitaka – Vibhanga-9 – Iddhipadavibhanga

51. Myanmar Tipitaka – Abhidhamma Pitaka – Vibhanga-10 – Bojjhangavibhanga

52. Myanmar Tipitaka – Abhidhamma Pitaka – Vibhanga-11 – Maggangavibhanga

53. Myanmar Tipitaka – Abhidhamma Pitaka – Vibhanga-12 – Ihanavibhanga

54. Myanmar Tipitaka – Abhidhamma Pitaka – Vibhanga-13 – Appamannavibhanga

55. Myanmar Tipitaka – Abhidhamma Pitaka – Vibhanga-14 – Sikkhapadavibhanga

56. Myanmar Tipitaka – Abhidhamma Pitaka – Vibhanga-15 – Patisambhidavibhanga

57. Myanmar Tipitaka – Abhidhamma Pitaka – Vibhanga-16 – Nanavibhanga

58. Myanmar Tipitaka – Abhidhamma Pitaka – Vibhanga-17 – Khuddakavatthuvibhanga

59. Myanmar Tipitaka – Abhidhamma Pitaka – Vibhanga-18 – Dhammahadayavibhanga

60. Myanmar Tipitaka – Abhidhamma Pitaka – Kathavatthu

61. Myanmar Tipitaka – Abhidhamma Pitaka – Puggalapannatthi

GUIDE TO TIPITAKA

Preface

The Tipitaka is an extensive body of Canonical Pali literature in which are enshrined the Teachings of Goiama Buddha expoumE!d for forty-f'ive years from \he time of his Enlightenment to his parinibbana. The discourses of the Buddha cover a wide field of subjects and are made up of exhortations, expositions and injunctions.

Even from the earliest times some kind of classification and systematization of the Buddha's Teachings had been mde to facilitate memorization, since only verbal transmission was employed to pass on the Teachings from generation to generation. Three IWnths a rter the parinibbana of the Buddha, the great disciples recited together all the Teachings of their Master, after compiling them systematical~ and carefully classifying them under different heads into specialized sections.

The general discourses and sernxms intended for bath the bhikkhus and lay disciples, delivered by the Buddha on various occasions ( together with a few discourses delivered by sOJOO of his distinguish6d disci~ plea ), are collected and classified in a great division known as the Suttanta Pit•aka • The great division in which nre incorporated injunctions and adJoonitions of the Buddha on modes of conduct, and restraints on both bodily and verbal actior of bhikkhus and bhikkhunls, which form rules of discipline for them, is called the Vinaya Pi~aka. The philosophical aspect of the Buddha IS TeaChing, IOOre profound and abstract than the discourses of the Suttanta Pi~aka, is classified under the great division known as the AbhidhaDm9 Pitaka. AbhidhallllIfl deals with ultimste Truths, expoums U• lti.uete Truths rind investigates Mind and Matter and the relntionship between them. All that the Buddha tauf'1t forms the subject DBtter and substance of the Pali Canon, which is divided 1nto these three divisions· called Pi~akas lite!' 8l.l¥ baskets. Hence Tipi~eka means three baskets or three separate div1eiona of the Buddha Is Teaching. Here GT, F.1 the metaphor 'basket' signifies not so much the funct.ion of 'storing up' anything put into it as its use 88 8 receptacle in which things are handed on or passed on from one to another like carrying away of earth from an exc!lvation site by a line of workers. The Tipit.aka into which the Pa.li Canon is ~ / 3Y15telMtically divided and handed down from generation' to gen~ration together with Commentaries forms the huge collection of literary works which the bhikkhus of the Order hDve to leern.. study and memorize in discharge of their gantha dhura .. the duty of studying • •

Acknowledgements

It is a great privilege for me to have been entrusted with the task of compiling this 'Guide to Tipi~akaI. So far as it is known.. there is not B single work that d~als, in outline, with the whole of Tipitaka. It is sincerely ooped that this compilCJtion will be found useful and hRndy by the general reader who wishes to be provided with a bird's eye view of the vast and magnificent canonical scenery which repres£:nts ell that the Buddha (am some of his disciples) had taught and. all that has been treasured in the Tipitaka.

In compiling this work, the Pall Texts as approved by the Sixth International 15uddhist S•ynod together with their BurlOOse translations have been closely adhered to. Acknowledgements are due to Dagon U San Ngwe and U Myo Myint who provided notes for soma of the chapters. Additional information and facts were gathered from various other .sources. The following couplete set of "Questions and Answers" recorded at the Sixth International Buddhist Synod proved to be a mine of information on the content. of the Tipi~aka.

1. Vinaya Pi~a1al - Questions and Answers, Volol

2. Vinaya Pit•aka - Questions and Answers .. Vol.II

3. Suttanta Pit•aka - lnighs NikSya' QAnusewsteirosn. s and

4. Sutt<lntA Pit•aka - 'Majjhia~ndNAiI<nasywaeIrsQ, uVesotli.oIns

3

5. Suttantt:l Pit•aka .' l'Djjhim<l NPonidkiAyan'sweQrsu,esVtiooln.sII

6. Suttanta Pitaka -ISa~tta Nikays 1 Questions

• and Answers, Vol.I

7. SuttRnta Pit8ka .1 S!ldvutta NikBya 1 Question8

• and Answers, Vol. II

8. Suttanta Pi~aka _IAllguttara Nikaya I Questions

nnd Answers, Vol.l

9. Suttanta Pi~aka _IAnguttara Nikaya

'

Questions

Rnd Answers, Vol.II

10. Abhidhamma Pitaka - IKhuddakn Nikaya I Questions

• and Ansv~rs.

Paragraph Nos. cited i~ this work ere from the

published Texts ;"lS approved by the Sixth International

Buddhist Synod.

In conclusion, I wish to put on record nv deep

gratitude to the members of the Editorial Committee,

Burma Pitaka Association, who had spent long hoors going

through the script ,'lith meticulous cnre and from whose

indefatigable labour :-md erudite counsel this c0II1>ilation

has much benefited •

•

February, 1984. U Ko Lay

4

•••

• • •

- Doctrina1 Adviser

i

Chairman

BURMA PITAKA ASSOCIATION

EDITORIAL COMMI'M'EE

Sayadaw U Kwnara, B.A.,

DhaDcariya

(SiromeQ!, Va~amsaka).

U Shwe Mra, B.A., I.C.S. Retd.;

Former Special Adviser,

Public Administration Division,

// E.S.A., United Nations

Secreta.ria.t.

Menmers • • •

• • •

• ••

UChan Htoon, LL.B., Barrister-

at-law; FOrmer President, World

Fellowship of Buddhists.

U Nyun, B.A., I.C.S. Retd.;

pormer Executive Secretary,

United Nations Economic Commission

for Asia and the Far

East; Vice-President, World

Fellowship of Buddhists.

U It'int Too, B.Sc., B.L.,

Barrister-at-law;

Vice-President, All Burma

Buddhist Association.

• ••

• ••

• ••

Doctrinal Consultant

Editors

Daw IVa Tin, M.A.,

Former Head of Geogr~phy

Department, Institute of

Education, Rangoon.

U ~aw Htut, Dhadcariya.

Former Editor-in-chief of the

Bo~rd for Burmese Tr~nslation

of the Sixth Synod Pali Texts.

U ~o Min, M.A., B.L.,·

Former Professor of English,

Rangoon UniYersity •

••• U Ko Lay, M.Sc.,

Former Vice-Ch~ncellor,

Mandalay University.

Secretarx.

• ••

• • •

•• •

U Thein Maung, B.h., B.L.

U tUa Maung, B"/1., B.L.

UTin IJwe, B.Se •

Chapter I

WHAT IS VINAYA PITAKA.?

•

Vinaya Pitaka

•

DiscipUnary and Procedur:Jl Rules for the Sa~ha

The Vina~a P1\aka is made up of rules of discipline

laid d0"lll for regulating the conduct of the Buddha's

di!ciples who have been admitted as bhikkhus and

bhikkhunIe into the Order. These rules embody authoritative

injunctions of the Buddha on JIDdes of conduct and

restraints on both physical and verbal actions. They

deal with transgressions of discipline, and with various

categories of restraints and admonitions in accordance

with the nature of the offence.

(a) Seven Kinds of Transgression or Offencc,Apatti

The rules of discipline first laid down by the

Buddha are called MUlapaMatti (the root regulation);

those supplemented later are kn-own as Anupai"lllatti. To- gether they are !mown as Sikkhapadas, rules of d:i~pline.

The act of transgressing these rules of discipline,

thereby-incurring a penalty by the guilty bhikkhu, is called Apatti .. which means 'reaching, committing'.

The of'tences for which penalties are laid down

may be classified under seven categories depending on

their nature:

(i}r~r~jika

lii)Samg~disesa

(iii) Thulla ccaya

(iv )P!ei ttiya

(v)P!~idesaniye

(vi)Dukka~a

(vii)Dubbh~sita.·

An offence in the first category of offences,

PAr~jika, is classified as a grave offence, garuk!patti,

which is irremediable, atekicchli and entails the• falling

off of the offen1er from bhikkhuhood. . - An offence in the second category, 5emghadisees

, is also classified as a grave offence but it 18

remediable,setekicch!. The offender is put on a probationary

period of penance, during which he has to

6

undertake cert3in difficult practices and after which

he is rehabilitated by the samgha assembly.

The rem~ining five categories consist of light

offences, lahukApatti, which Are remediable and incur

the penalty of having to confess the transgression to

lnother bhikkhu. After carrying out the prescribed pen~

lty, the bhikkhu transgressor becomes cleansed of the

C'rfenc~.

(b) When and how the disciplinary rules were laid down.

For twenty years after the establishment of the

Order there was neither injunction nor rule concerning

P5rajika and Ssmgh8disess offences. The members of the

Order of the early days were all Ariyns, the least advanced

of whom was ~ Strea~winner, on~ who had attained

th~ first MDgga ~nd ~Tuition,and there was no need for

prLsoribing rules relating to grave offences.

But as the years went by, the Samgha grew in

strength. Undesirable elements not having the purest of

motives but attracted only by the fame 3nd gain of the

bhikkhus beg~n to get into the Buddha's Order. Some

twenty years after the founding of the Order, it becama

necessary to begin establishing rules relating to grave

offences.

It was through Bh-ikk-hu Sudinna, a native of K3landa Village near Vesali, who committed the offence

of having sexual intercourse with his ex-wife, that the

first P~rajika rule came to be promulgated. It was laid

down to deter bhikkhus from indulging in sexual intercourse

•

When such a grave cause had arisen for which the

iaying down of a prohibitory rule became necessary, the

Buddha convened an assembly of the bhikkhus. It was only

after questioning the bhikkhu concerned and sfter the

undesirability of committing such an offence had been

made clear that a certain rule was laid down in order to

prevent future lapses of similar nature.

The Buddha also followed the precedence set by

earlier Buddhas. Using his supernormal powers, he reflected

on what rules the earlier Buddhas would lay

down under certain given conditions. Then he adopted

similnr regulations to meet the situation that had

aris,-'!: in his time.

7

(c) Admission of bhikkhunIs into the Order

Arter spending four vassas (residence period

during the rains) after his Enlightenment, the Buddha

visited Kapilavatthu, his native royal city, at the request

of his ailing father, King Suddhodana. Ai.. 'that

time, MaMpejapati, Buddha's foster IOOther requested

him to admit her into the Order. MaMpajap8ti was not

alo~e in desiring to join the Order. Five hundred Sa~an

lad1es whose husbands had left the household life were

also eager to be adJl1.tted into the Order.

After his father's death, the Buddha went back

to V~s8l!, refusing the repeated request of MaMpaj!pati

for admission into the Order. The determined foster

m:>ther of the Buddha and widow of the recently de~ea8ed

King Suddhodana, having cut orr ber hair and put on

bark~ed clothes" accoq>anied by five hundred sa~an

ladies, made her way to Vesalr where the Buddha was

staying in the MaMvana, in the KuUg§ra Hall.

The Venerable Ananda saw them outside the gateway

of the KiiUg!ra Hall, dust-laden with swllen feet, dejected,

tearful, standing and weeping. Out of great compassion

for the ladies, the Venerable AnaDda interceded

with the Buddha on their behalf' and entreated him to

accept them in the Order. '!he Buddha continued to stand

firm. But when the Venerable Anandai asked the Buddha

whether women were not capable of attaining Magga and

Phala Insight, the Buddha replied that women were indeed

capable of doing so, provided they left the household

life like their menfolk.

Thereupon ADama made his entreaties again saying

that MaMpaj'pati had been of great service to the Buddha

waiting on him as his guardian and nurse, suckling

him when his mther died. And as women were capable of

attaining the Magga and Phala Insight, she should-be permitted to join the Order and become a bhikkhuni.

The Buddha fina1J¥ acceded to AnancUl l s entreaties:

"Xnanda, if lot1Mpaj~pati accepts eight special rules,

garu-dha~, let such acceptance mean her admission to

the Order."

The eight special ruleJ are:

(1) A bh1kkhunI, even if she enjoys a seniority of

a hundred years in the Order, mus't pay respect

1. vide, Vin&y& - II, 74-75.

8

to a bhikkhu though he may have been a bhikkhu

only for a day.

(ii) A bhikkhunI must not keep her rains-residence in

a place where there are no bhikkhus.

(iii) Every fortnight a bhikkhunI must do two things:

To ask the bhikkhu Ssmgha the day of osa ,

and to approach the bhikkhu samghs for instruction

and adJoonition.

(iv) When the rains-residence period is over, a bhikkhuni

must attend the yav~rau~ ceremony conducted

at both the assemblies of bhikkhus and bhikkhunIs,

in each of which she must invite criticism on what

has been seen, what has been heard or what has

been suspected of her.

(v) A bhikkhunI who has co~tted a saffighadisesa

opaffkeknhcaem-m-aunsatttuan, dienrgoeacphenaasnsceemfbolyr oa fhbahlfi-krkrhcunstha, nd bhikkhunis.

(vi) Admission to the Order n~st be sought, from both

assemblies, by a woman novice only after two

year's prcbationary training IlS c candidate.

(vii) A bhikkhun-i should not revile a bhikkhu in any

way, not even obliquely.

(viii) A bhikkhunI must abide by instructions given her

b~ bhikkhus, but must not give instructions or

advice to bhikkhus.

~~hapajapati accept0d unhesitatingly these eight

conditions imposed by the Buddha and was consequently

admitted into the Order.

9

Chapter II

VINAYA PITAKA

•

The Vinaya Piteka is mde up of five books:

•

(1) P-arajika Pa.li. 2 Pac-ittiya P~_l..i 34 MC-ualhaavvaaggggaa PP-aa"ll1i

5 Pa•riva- ra P-alIi

•

1. Parajika Pali

•

Parajika Pali which is Book I of the Vinaya P1.taka gives an ela•borate explan-at-ion of the impo-rtant rules of discipline concerning FarAji~~ and sa~~hadisesa,

as well as Aniyeta I'lnd Nissaggiyc which fJre minor

offences.

(a) Parajika offences ?nd penalties.

- - Paraji~1 disciplin0 consists of fow' sets of

rules laid down to prevent four gravG offences. Any

transgressor of these rules is defe~ted in his purpose

Pin-ar-baejickoacinA-gpaattbi hfikakllhsu. upInonthheimp; ahrelan,1cuetomocfltiVcianlalyya, lothsees

the status of e bhikkhu; he is no longer recognized as

a member of the community of bhikkhus nnd is not permitted

to become a bhikkhu again. He has either to go back

tsotatthues ohofuasesh-aomldn•leirfae, aas.n'O) Vl.1acyem•9n or revert back to the

One who has lost the status of a bhikkhu for

transgression of any of these rules is likened to (i)

a person wrose head has been cut off from his body; he

cannot become Dlive even if the head is fixed back on

the body; (ii) leaves which have fallen off the branches

of the tree; they will not become green a~ain even if

they are attached back to the leaf-stalks; (iii) a flat

rock which has been split; it cannot be Ji\,.de whole again;

(1v) a palm tree which has been cut off from its stem;

it will never grow again.

Four P~rajika offences which lend to loss of

stc?tus as a bhikkhu.

(1) The first Pari3jika: Whatever bhikkhu should indulge

in sexual intercourse loses his bhikktn.1OOod.

10

(ii )

(11i)

- - The second Parajika: Whatever bhikkhu should take

with intention to steal what is not given loses

his bhikkhuhood.

The third Parajik8 ~ Whatever bhikkhu flhould intentionally

deprive a hwmn being of life loses his

bhikkhuhood.

(iv) The fourth P-ar-ajika: Whatever bhikkhu claims to

attainments he does not really possess, namely,

attainments to jhana or l-bgga and Ptulla Insight

loses his bhikkhuhood.

The pirijika ot!ender is guilty of a veq grave

tran6gression. He ceases to be a bhikkhu. His offence,

lpatti, is irremediable.

(b) Thirteen Samgh~sesa offences and penalties.

Samghadisesa discipline consists of a set of

thirteen rules which require formal participation of the

Samgha from beginning to end in the process of mnkir€

him free from the guilt of transgression.

(i) ~ bhikkhu having transgressed these rules, and

wishing to be free from his offence must first

3pproach the Samgha and confess having comnitted

the offenc~. The Samgha determines his offence

Jnd orders him to observe the pariv~sa penance,

~ penalty requiring him to live under suspension

from association with the rest of the Samgha, fer

"s mal\Y days as he hns knowingly concenled hi$

r>ffence.

(ii)

(iii)

At the end of the parivasa observance he undergoes

a further period of penance, man~ttaJ for

six days to gain approbation of the saJiJgha.

Having carri~d out the m§natta penance, the bhikkhu

requests the SaIhgha to reinstate him to full

association with the rest of the Samgha.

Being now convinced of the-purity of his conduct as before, the samgha lifts the Apatti at a special congregation

attended by at least twenty bhikkhus, where

netti, the rotion for his reinstate~nt, is recited followed

by three recitals of kammav~c~, procedural text for

f0rIl81 acts of the samgha.

11

Some examples of thf saIhghadises.1 offtnces.

(i) Kayasamsagga offence: .,

If any bhikkhu wi th lustful, perverted thoughts

engages in bodily contact with a woman, such as

holding of hands, caressing the tresses of hair

or touching any part of her body, he commits the

Kayasamsagga 5albghSdisesa offence.

(ii) Sancaritta offence:

If any bhikkhu acts as a go-between between a man

and a womnn for their lawful living together as

husband and wife or for tempor.'lry arrangement as

man and IIii.stress or WOIrr3n and lover, he is guilty

of Sancaritta Samghadisesa offence. '

(e) Two Aniyata offences and penalties.

Aniyata means indefinite, uncertain. There are

two Aniyata offences the nature of which is uncertain

and indefinite as to whether it is a Parajika offence,

a Samghadisesa offence or a Pacittiya offence. It is

to be determined according to provisions in the following

rules:

(i) If a bhikkhu sits down privately alone with a

woman in a place which is secluded and hidden

from view, and convenient for an illllIOral purpose

and if a trustworthy Uu WOIllt1n (i.e., an Ariya)"

seeing him, accuses him of any one of the three

offences (1) a Parajika offence (2) a Sarnghadisesa

offence (3) a Facittiya offence, and the bhikkhu

himself admits that he was so sitting, he should

be found guilty of one of these three offenoes as

accused by the trustworthy lay woman.

(ll) If a bhikkhu sits down privately alone with a

womn in a place which is not hidden from view

and not convenient for an ilIl1'OOral purpose but convenient

for talking lewd words to her" ''!Od if a

trustworthy lay woman (i.e., an Ariya), seeing him,

accuses him of anf one of the two offences (1)

a sa~hadisesa offence (2) a P~cittiya offence,

and the bhikkhu himself admit~ th~t he was so

sitting, he should be found guiltY! f one of

these two offences as accused by tH trustworthy

lay woman.

12

(d) Thirty Nissaggiya Pacittiya offences and penalties.

There are thirty rules under the Nissaggiya category

of offences and penalties which are laid down to

curb inordinate greed in bhikkhus for possession of

material things such as robes, bowls etc. To give an

example, an offence is done under these rules when

objects not permitted are acquired, or when objects are

acquir0d in more than the permitted quantity. The penalty

consists firstly of giving up the objects in respect

of which the offence hAS be~n committed. Then it

is followed by confession of th~ breach of the rule,

together with an undertaking not to repeat the same offence,

to the Samgha as 8 whole, or to a group of bhikkhus,

or to an individual bhikkhu to whom the wrongfully

acquired obj~cts have been surrendered.

Some examples of the Nissaggiya P-acittiya

offences.

(i) First Nissaggiya Sikkhapada.

If arw bhikkhu kl::eps more thdrl the permissible

number of robes, namely, the lower robe, the upper

robe and the great robe, he comnits an offence

for which he has to st~rl::ndcr the extra

robes and confess his offence.

(ii) CIvara Acchindana Sikkhapada.

If arw bhikkhu gives away his own robe to another

bhikkhu and aftcnrords, being angry or displeased,

atawkayesbyit sobmacekonefoerclsibel,y hEo: rcocmaumsietss ait NtiossbaeggtiaykaenP-acittiya

offence.

wNiits.hsagt-hg8iyagraovffe-enocf8fesncaeres olifghpatroajffie~n1cA-espactotmi poarred Samghadisesa Apatti.

2. Pacittiyn Pali

•

The Pacittiya P~li which is Book II of the Vinaya

• Pit.aka d~als with the r8maining sets of rules -for the bhikkhus, namely, the P~cittiya, the P~tidesaniya,Sekhiya,

Adhikaranasamatha and the corresponding disciplinary

rules for th~ bhikkhunIs. Although it is called in

P~li just P~cittiya, it has the distinctiv8 nam~ of 'Sud-

• dha P~cittiya', ordin2ry P~cittiya, to distinguish it

from Nissaggiya P~cittiya, describ~d ~bove.

(8) Ninety-two PAcittiya offences and penalties.

There are ninety-two rules und~r this class of

offences classified in nine sections. A few examples of

this type of offences:

(i) Telling a lie deliberately is ~ P5cittiya offence.

(ii) A bhikkhu who sleeps under the sam" roof and within

the walls along with a wonen commits a P~cittiya

offence.

(iii) A bhikkhu who digs the ground or c~uses it to be

dug commits a ~cittiya offence.

A Pacittiya offence is remedied ncrely by Cldmission

of the offence to a bhikkhu.

(b) Four P§tidesanIya offences and pen~lties•

•

There, are four offences under this classification

and they all deal with the bhikkhul s conduct in accepting

and eating alms-food offered to him. Thl: bhikkhu .

transgressing any of these rules, in 1n'J kinG admission of

his offence, must use a special formul~ stating the natur~

of his fault.

- The first rule of P~tidcsuniya offence reads:

should a bhikkhu eat hard food or soft food having

accepted it with his own hand from a bhikkhunI who is

not his relation and who has gone alIDng the houses for

alms-food, it should be admitted to another bhikkhu by

the bhikkhu saying, "Friend, I have done a censurable

thing which is unbecoming and which should be admitted.

I admit having committed a P§tidesanIya offence."

•

The events that led to the l-ay~ng down of the first of these rules happened-in savatthi, wherE. one IOOrning bhikkhus and bhikkhun-is were going round for alms-food. A certain bhikkhuni offered the food she had

received to a certain bhik-khu who took away all that was in her bowl. The bhikkhuni had to go without ~lny food

for the day. Three days in succession she offered to

give her alms-food to the same bhikkhu who on all the

three days deprived her of her entire alms-food. Con

·sequently she became famished. On the fourth day while

going on the alms round she fainted and fell down

through weakness. When the Buddha caml: to hear about

this,be censured the bhikkhu woo was guilty of the wrong

deed and laid down the above rule.

14

(c) Seventy-five Sekhiya rules of polite behaviour.

These seventy-five rules laid down originally for

the proper behaviour of bhikkhus also apply to novices

who seek admission to the Order. l-bst of these rules

were all laid down at savatthi on account of indisciplined

behaviour on the part of a group of six bhikkhus.

The rules can be divided into four groups. The first

group of twenty-six rules is concerned with good conduct

and behaviour when going into towns and villages. The

second group of thirty rules deals with polite manners

when accepting alms-food and when eating meAls. The third

group of sixteen rules contains rules which prohibit

teaching of the Dhamma to disrespectful people. The

fourth group of three rules relates to unbecoming ways

of answering the calls of nature and of spitting.

(d) Seven ways of settling disputes, Adhikaranasamatha •

•

, P~cittiya Pali concludes the disciplinary rules

for bhikkhus with a •Chapter on seven ways of settling

cases, AdhikarAnasamatha •

•

Four kinds of cases are listed:

(i) VivMadhikarAna Disputes as to what is dhamma,

what is not dhammaj what is Vinaya, what is

not 'Vinaya; what the Buddha said, what the Buddha

did not say; and what constitutes an offence,what

is not an offence.

(ii) Anuv~dadhikarana Accusations and disputes

arising out of·them concerning the virtue, practice,'

views and way of living of a bhikkhu.

(iii) Apattadhikarana Infringement of any disciplinary

rule ••

(iv) Kiccadhikarana Formal meeting or decisions

made by the Samgha. ,.<

For settlement of such disputes that may arise

from time to time amongst the Order, precise and detailed

methods are prescribed ur~er seven heads:

(i) Sammukha Vinaya before coming to a decision,

conducting an enquiry in the presence of both

parties in accordance with the rules of Vinaya.

(ii) Sati Vinaya making a declaration by the

Samgha of the innocence of an Arahat 'against

1 5

whom some allegations have been made, afte~ asking

him if he remembers having committed the off~nce.

(iii) Am\i+ha Vinaya making a declaration by thE;

Samgha when the accused is found to be insane.

(iv) PatiMUa KaraI}a making a decision after

admission by the party concerned.

(v) Yehhuyyasika Kamma making a decision· in

accordance with the majority vote.

(vi) Tassap~piyasika Kamma making a declaration by

the 5amgha when th~ accused proves to be un.~liable,

making admissions only to retract them,cvading

questions and. telling lies.

(vii) TinavattMraka Kamma 'the act of covering up

with grass' exonerating all-offences except the offences of ~rajika, 5amghadisesa and tt~S(;

in connection with laymen and laywomen, when thE:

disputing parties are made to reconcile by the

samgha.

(e) Rules of Discipline for the bhikkhunIs.

The concluding chapters in the Pllcittiya PDF are

devoted to the rules of Discipline for the bhikkhunIs.

The list of rules for bhikkhunIs runs longer than that

for the bhilckhus. The bhikkhunI rules were drawn up on

exactly the same lines as those for the bhikkhus, with

the exception of the two Aniyata rules which are not

laid down for the bhikkhunI Order.

- Bhikkhu Bhikkhuni

(1) P!r!jika 4 8

(2) . - SBmghadisesa 13 17

(3) Aniyata 2 - (4) Nissaggi~ P!cittiya 30 30

(5) Suddha Pacittiya 92 166

(6) - - Pat-idesaniya 4 8

(1 ) Sekhiya 75 7,

(8) Adhikarana samatha 7 7

227 311

• -

These eight categories of disciplinary rule~ for

bhikkhus and bhikkhwUs of the Order are treated in cletail

in the first two books of the Vinaya Pitaka. ~or

16

each rule an historical account is given as to how it

comes to be laid down, followed by an exhortation ot the

Buddha ending with "This offence does not lead to rO\l8ing

of faith in those who are nbt convinced of the Teaching,

nor to increase of faith in those who are con ..

~ed." After the exhortation comes the particular rule

l:a1d down by the Buddha followed by word for word cu.

mental")" on the rul:e.

J. ltlha-vagga Pall.

o

The next tw-o books, -namely, Mah!vagga PA.li which is Book III and C$vagga Pall which is Book IV of the

Vineya Pi1Caka, deal with aU'those I1Btters relating to

the Sa!lgha which have not been dealt with in the first

two books.- - !ehavagga Pali, made up of ten sections known as

Khandhakas, opens with an historical account of how- the

Buddha attained Supreme Fnlightenment at the foot of tbe

Bodhi Tree, how he discoYered the famous law of Dependent

Origination, how he gave his first sermn to the

Group of Five Bhikkhus on the discovery of the Four

Noble Truths, namely, the great Discourse on The Turning

of the Wheel of Dhamma, Dhammacakkappavattans Sutta.nus

was followed by arother great discourse, the AnattalakkhsJlB

Sutta. These two suttas my be described as the

Coq,endium of the Teaching of the Buddha.

The first section continues to describe how young

men of good families like Yass sought refuge in him as

a Buddha and embraced his Teaching; how the Buddha embarked

upon the unique mission of spreading the Dhamma

Ifor the welfare and. happiness of the many I when he had

collected round him sixty disciples who were well established

in the DhaJllM and had become Arahats; how he

began to establish the Order of the sa~a to serve as a

living example of the Truth he preached;· aoo how his

fallD-us disciples like ~riputta, l-k:>ggallAna, ~ha Kassa- pa, Ananda, Upall, Arigulim!!la became members of the Or~

der. The same section then deals with the rules for

formal admission to the Order, (Upasampada), giving precise

conditions to be fulfilled before any person can

gain admission to the Order and the procedure to be

followed for each admission.

M:l~vagga further deals with procedures for an

17

t.!Wsatha meting, the assenb~ of the Samgha on every f'u11

JDl)()D day and on the folD"teeDt.b or titteenth ~n1ng day of

the lunar montb when Pitimkkha, • SWIID8I7 of the Vinaya

rules, is recited. Then there ar~ rules to be observed

for rains retreat (vassa) during the rainy season as well

as those for the formal cereJIDIV of pavarana concluding

the rains retreat, in which a bhikkhu invites criticism

from his brethren in respect of what has been seen, heard

or suspected about his conduct.

There are also rules ooncerning si~k bhikkhus,

the use of leather for footwear and furniture, materials

for robes, and those concerning medicine and food. A

separate section deals with the ceremonies where

annual making and offering of robes take place.

- - . 4. Cutavagga Pa~~ - - Cutavagga PaU which is Book IV of the Vinaya Pitaka

continues to deal with m.:>re rules and procedures for

institutional acts or functions la:own as satilghakamma.The

twelve sec.tion-s in this book deal with rules .for offences such as Samghadisesa that come before the Samgha; rules

for observance of penances such as parivasa and Inanatta

and rules for reinstat~mcnt of a bhikkhu. There are also

miscellaneous rules concerning bathing, dress, dwellings

and furniture and those dealing with treatment of visiting

bhikkhus, and duties of tutors and novices. Som-e of the important enactrrents are concerned with Tajjaniya

Kama, formal act of censure by the SAmgha taken against

those bhikkhus who cause strife, quarrels, disputes, who

associate familiarly with lay people and who speak in

dispra-ise of the Buddha, the Dhamma Clnd the satbgha; Uk- khepaniya Kamma, formal act of suspension to be taken

against those who having committed an offence do not want

to admit it; and PakB'samya KaITllllD taken against Devadatta

announcing public1¥" that "Whatever Devadatta does by deed

or word, should be seen as Devadatta I s own and has nothing

to do with the Buddha, the Dhamma and the saffigha."

The account of this action is followed by the story of

Devadatta1s three attempts on the life of the Buddha and

the schism caused by Devadatta aoong the Sarngha.

There is, in section ten, the story of how Mahapaj

§pati, the Buddha's foster mother, requested admission

into the Order, how the Buddha refused permission

GT, F.2

18

at first, and how he finally acceded to the request because

of Ananda1s entreaties on her behalt.

The lest two sections describe two i~rtant

events of historical interest, namely, the holding of the

first Synod at R8jagaha and of the seCond Synod at VeealI.

- - 5. Parivara Pali

• •

Parivara Pali which is Book V and the last book of

theV1nayaPit:aka series as a kind of manual. It is compiled

in the form of a catechism, enabling the reader to make

an analytical survey of the Vinaya Pitaka. All the rules,

official acts, and other matters of tne.Vinaya are class~

fied under separate categories according to subjects

dealt with.

- Parivara explains how rules of the Order are drawn

up to regulate the conduct of the bhikkhus as well as the

administrative affairs of the Order. Precise procedures

are prescribed for settling of disputes and handling

matters of jurisprudence, for fornation of Samgha courts

and appointment of well-qua lined Saffighn jUd~es. It lays

down how Salngha Vinicchaya Committee, the Samgha court,

is to be cODstituted with a body of learned Vinayadharas,

experts in Vinaya rules, to hear and decide all kinds of

monastic disputes.

The Parivara Pali provides general principles and

guidance in the spirit ·of which all the 5amgha Vinicchaya

proceedings are to be conducted for settlement of monastic

disputes.

19

Chapter III

WHAT IS SUTTANTA PITAKA? •

The Suttanta Pitaka is a collection of all the

discourses in their eniirety delivered by the Buddha on

various occasions. (A few discourses delivered by some

of the distinguished disciples of the Buddha, such as the

Venerable sariputta, Maha Moggal18na, Ananda, etc.Jas

well as some narratives are also included in the books

of the Suttanta Pitaka.) The discourses of the Buddha

compiled together in the Suttanta Pitakn were expounded

to suit different occasions, for various persons with

different temperaments. Although the discourses were

mostly intended for the benefit of bhikkhus, and deal

with the practice of the pure life and with the exposition

of the Teaching, there are also several other discourses

which deal with the ~1terial and moral progress

of the lay disciples.

The Suttanta Pitaka brings out the meaning of the

Buddha1s teachings, exPresses them clearly, protects and

gua~ds them against distortion and misconstruction. Just

like a string which serves a s a plumb-line to guide the

carpenters in their work, just like a thread which protects

flowers from being scattered or dispersed when

strung together by it, likewise by means of 8uttas, the

meaning of Buddha's teachings may be brought out clear~,

grasped and understood correctly and given perfect protection

from being misconstrued.

The Suttanta Pitaka is divided into five s~parate

collections known as Nik.i;ras. They are Digha Nikiya I

Hajj hima Nikiya, Saliwutta Nikiya, Ailguttara Nikiya

and Khuddaka Nikiya.

(a) Cbservances and Practices in the Teaching of

the Buddha.

In the Suttanta Pitaka are found not only thE:

fundamentals of the DhalllIll8 but also pragmtic guidelines

to IMke the Dhamn:a meaningful and applicable to daily

life. All observances and practices which form practical

steps in the Buddha's Noble Path of Eight Constituents

lead to spiritual purification at three lev~ls: - Sila moral purity through right conduct,

PAnna

samadhi

20

purity of mind through concentration

(Samth:)) ,

purity of Insight through Vipp.ssana

Meditation ..

To begin with, one must make th~ right resolution

to take refuge in the Buddha, to follow the Buddha's

Teaching, and to be guided by the saffigha. The first disciples

who made the declaration of faith in the Buddha

and committed themselves to follow his Teaching were the

two merchant brothers, Tapussa and Bhallika. They were

travelling with their followers in five hundred carts

when they saw the Buddha in the vicinity of the Bodhi

Tree after his Enlightenment. The two merchants offered

him honey rice cakes. Accepting their offering and thus

breaking the fast he had imposed on himself for seven

weeks, the Buddha made them his disciples by letting them

recite after him:

11 Buddham Sar<J !';lam Gac chami (I ta ke re fuge in

t he Buddha).1I

11 Dhamr:Jc::ltl SDra~om Gacchnmi (I take refuge in

the Dha I1Irl;) ) • It

This recitation became the formula of declaration

of faith in the Buddha and his Teaching. Later when the

Saffigha became established, the formula was extended to

include the third commitment:

It Samgham Saranam Gacchami (I take refuge in

the S<:!n,.gha). 11'

(b) On the right way to give alms.

As a practical step, capable of immediate and

fruit.ful use by people in all walks of life, the Buddha

gave discourses on charity, alms-giving, explaining its

virtues and on the right way and the right attitude of

mind with which an offering is to be made for spiritual

uplift.

The :!lOtivating force in an act of

volition, the will to give, Charity is a

action that arises only c~t of volition.

will to give, there is no act uf giving.

giving alms is of three types:

charity is the

meritorious

Without the

Volition in

21

(i)

(ii)

(iii)

The volition that starts with the toought 'I shall

make an offering' and that exists during the period

of preparations for making the offering --PubbaCetana,

volition before the act.

The volition that arises at the rooment 01 making

the offering while handing it over to the donee

Mufica Cetan~, volition during the act•

• The volition accomparwing the joy ani rejoicing

which arise during repeated recollection of or

reflection on the act of giving - Apara Cetana,

volition after the act.

Whether the offering is nede in homage to the

living Buddha or to a minute particle of his relics after

his passing away, it is the volition, its strength and

purity that determine the nature of the result thereof.

There is also explained in the discourses the

wrong attitude of mind with which no act of charity

should be performed.

A donor should avoid looking down on others who

cannot make a similar offering; nor should he exult over

his own charity. Defiled by SlAch unworthy thoughts, his

volition is on~ of inferior gradG.

When the act of charity is motivated by expectations

of beneficial results of immediate prosperity and

happiness, or rebirth in higher existences, the acco~

parwing volition is classed as mediocre.

It is only when the good deed of alms-giving is

performed out of a spirit of renunciation, motivated by

thoughts of pure selflessness, aspiring only for attain!

rent to Nibbana where all suffering ends, that the voll~

tion that brings about the act is regarded as of superior

grade.

Examples abound in the discourses

charity and IOOdes of giving alms.

concerm•ng

(c) Moral Purity through right conduct, Sila. - Practice of sUa forms a lJX)st fundamental aspect

of Buddhism. It consists of practice of Right Speech,

Right Action and Right Livelioood to purge oneself of

impure deeds, words and tho •

mitment to the Threefold Ref ~'tIWAp.~lPil:J!ta Rt189e.~°ft lind

PropJg.uion 0" the ~ ..sana

liBRARY

Kaba-Aye. Yangon.

22

BUddhist lay disciple observes the Five ~recepts by

making a formal vow:

(i) I undertake to observe the precept of abstaining

from killing,

(ii) I underta ke to observe the precept of abstaining

fr.')m stealing.

(iii) ..L undertak8 to observe the precept of abstaining

from sexual misconduct.

(vi) I undertake to observe the precept of dbstaining

from telling lies.

(v) I undertake to obs~rve the precept of abstaining

from alcoholic drinks, drugs or intoxicants that

becloud the mind.

In addition to the negative aspect of the above

pfoorsmituilvaewahsipchecetmopfhass-iilzae.s aFborstiinnesntacnec, e, thVIeerefinids ainlsomatnhye

discourses the statement: 'He refrains from killing, puts

aside the cudgel and the sword.; full of kindness and cornpassion

he lives for the welfare and happiness of all

living things.' Every precept laid do~m in the formula

has these two aspects.

Depending upon the ,individual and the stage of

one's progress, other forms of precepts, namely, Eight

Precepts, Ten Precepts etc. may be observed. For the

bhikkhus of the Order, higher and advanced types of practices

of morality are laid down. The Five Precepts are

to be always observed by lay disciples who may occasionally

enhance their self-discipline by observing the

Eight or Ten Precepts. For those who have already embarked

on the path of a holy life, the Ten Precepts are

essential preliminaries to further progress.

8-ila of perfect purity serves ~s a foundation for

the next stage of progress, namely, Samadhi purity

of mind through concentration-meditation.

(d) Practical methods of r.lental cultivation for development

of concentration, sarnadhi.

Mental cultivation for spiritual uplift consists

of two steps. Th(; first step is to purity the mind from

all defil~ments and corruption and to have it focused on

2)

a point. A determined effort (Right Exertion) must be

made to narrow down the range of thoughts in the wavering,

unsteady mind. Then attention (Right Mindfulness or

Attentiveness) must be fixed on a selected object of

meditation until one-pointedness of mind (Right ~oncentration)

is achieved. In such a state, the mind becomes

freed from hindrances, pure, tranquil, powerful and

bright. It is then ready to advance to the second step

by which Hagga Insight and Fruition may be attained in

order to transcend the state of wpe and sorrow.

The Suttanta Pitfaka records numerous methods of

meditation to bring about one-pointedness of mind. In

the auttas of the Pitaka are dispersed these methods of

maditation, explained by the Buddha sometimes singly,

sometimes collectively to suit the occasion and the purpose

for which they are recommended. The Buddha knew the

diversity of character and mental make-up of each individual,

the different temperaments and inclinations of

those who approached him for guidance. Accordingly he

recommended different methods to different persons to

suit the special character and need of each individual.

The practice of mental cultivation which resul-ts ultimately in one-pointedness of mind is known as Samadhi

Bhllvana. Whoever wishes to develop Samadm. Bh~yana must

have been established in the observance of the precepts,

with the senses controlled, calm and self-possessed, and

must be contented. Having been established in these four

conditions he selects a place suitable for meditation, a

secluded spot. Then he should sit cross-legged keeping

his body erect and his mind alert; he should start purifying

his mind of five hindrances, namely, sensual desire,

ill will, sloth and torpor, restlessnes6 3nd worry, and

doubt, by choosing a meditation method suitable to him,

practising meditation with zeal and ardour. For instance,

with the Anapana method he keeps watching the incoming

and outgoing breath unti:l he can have his mind fixed

securely on the breath at the tip of the nose.

When he realizes that the five hindrances have

been got rid of, he becomes gladdened, delighted, calm

and blissful. This is the beginning of sanadhi, Concentration,

which will further develop until it atta~ns

one-pointedness of mind.

Thus one-pointedness of mind is concentration of

24

mind when it is aware of one object, and only one of a

wholesome, salutary nature. This is attained by the

practice of meditation upon one of the subjects reco~

mended for the purpose by the Buddha.

(e) Practical methods of mental cultivation for development

of Insight Knowledge, panna.

The subject and m~thods of meditation as taught

in the suttas of the Pitaka are designed both for attanr • ment of samadhi as well as for development of Insight

Knowledge, Vipa ssana Nal}Cl, a s a direct pnth to rJibbana.

As a second step in the practice of meditation,

after achieving samadhi, when the concentrated mind has

become purified, firm and imperturbable, the meditator

directs and inclines his mind to Insight Knowledge, Vipassana

Na~a. With this Insight Knowledge he discerns

the three characteristics of the phenomenal world, namely.

Impermanence (Anicca), Suffering (DillG<ha) and Non-Self

(Anatta) •

As he advances in his practice and his ~ind becomes

more and more purified, firm 3nd i~erturbable,

he directs and inclines his mind to the knowledge of the

extinction of moral intoxicants, Asavakkhaya Nal}Cl. He

then truly understands dukkha, the cnuse of dukkha, the

cessation of dukkha and the path leading to the cessation

of dukkha. He also comes to understand fully the moral

intoxicants (asavas) as they really are, the cause of

aSaV8S, the cessation of asuvas and the path leading to

the cessation of the asavas.

With this knowledge of extinction of asavAs he

becomes libergted. The knowledge of liberation arises

in him. He knows that rebirth is no more, that he has

lived the holy life; he hns done whnt he has to do for

the realization of l~gga; there is nothing more for him

to do for such realization.

The B~ddha taught with only one object the

extinction cf Suffering and release from conditioned

existence. That object is to be obtained by the practice

of meditation (for Calm and Insight) as laid down in

numerous suttas of the Suttanta Pitaka •

•

25

Chapter IV

SUTTANTA PITAKA

. - D~gha Nikaya

Collection of Long Discourses of the Buddha

This Collection in the Suttanta Pitaka, named

nIghs Nikaya as it is made up of thirty-foUr long discourses

of the Buddha, is divided into three divisions:

(a) Silakkhandha. Vagga, Division Concerning Morality

(b) Maha Vagga, the Large Division (c) Pathika Vagga,

the Division beginning with the discourse on Pathika,

the Naked Ascetic.

(a) Sllakkhandha Vagga Fa~i

Division Concerning Morality

This division contains thirteen suttas which

deal extensively with various types of TOClrality, namely,

Minor M:>rality, basic morality applicable to all; Middle

Morality and Major Morality which are most1¥ practised

by Samanas and Br~hmanas. It also discusses the

wrong views tnen prevalent as well as brahmin views of

sacrifice and caste, and various religious practices

such as extreme self-mortification.

(1) - Net of Perfect Brahmajala Sutta, Discourse on the

Wisdom.

An arg~ent between Suppiya, a wandering ascetic,

and his pupil Brahmadatta, with the teacher maligning

the Buddha, the Dhamma and the safugha and the pupil

praising the Buddha, the Dhamrna and the Samgha gave

rise to .t.his famous discourse which i~ listed first in tb1s Nikaya.

In connection with the maligning of the Buddha,

the Dhamna and the samgha, the Buddha enjoined his disciples

not to feel resentment, nor displeasure, nor anger,

because i~ would only be spiritual1¥ harmful to

them. As to the ~ords of praise for the Buddha, the

Dhamma and the sa~ha, the Buddha advised his disciples

26

not to feel pleased, delighted or elated, for it would

be an obstacle to their progress in the Path.

The Buddha said that whatever worldling, puthujjana,

praised the Buddha he could not do full justice to

the peerless virtues of the Buddha, namely, his Superior

Concentration, samadhi, and Wisdom, pann~. A worldling

could touch on only "matters of a trifling and inferior

nature, IOOrc oorality." The Buddha explained the three

grades of morality and said that there were other dha~

mas profound, hard. to see, subtle and intelligible on~

to the wise. Anyone wishing to praise correctly the true

virtues of the Buddha should do so only in terms of

these dhanunas.

Then the Buddha continued to expound on various

wrong views. There were samanas and br~hmanas who,speculating

on the past, adhered to and asserted their wrong

views in eighteen different ways, namely,

(i) Four Kinds of Belief in Eternity, sassata

Ditthi,

(ti) Four Kinds of Dualistic belief in Eternity and

Non-eternity, Ekacca Sasesta Ditthi,

••

(iii) Four Views of the World being Finite or

Infinite, AnMnanta Ditthi,

• •

(iv) Four Kinds of ambiguous evasion, Amaravikkhepa

VSda,

(v) Two Doctrines of Non-Causality, Adhiccasamupparma

vada.

- There were samanas and brahmanas, who, speculating

on the future, adhered to and asserted their wrong

views in forty-four ways, namely,

(i) Sixteen Kinds of Belief in the Existence of

Sanna after death, Uddha~gh~tanikD Sanfli vada,

(ii) Eight Kinds of Belief in the NOn-Existence of

Sanna after death, Uddhamaghatanika Asa~ Vada,

(iii) Eight Kinds of Belief in the Existence of

Neither sa~ Nor Non-so~a after death,

Uddhamaghatanika Nevasafini N~saBni Vada,

(iv) severt' Kinds of Belief in Annihilation, Uccheda

Vada, .~

27

(v) Five Kinds of Mundane Nib~na as realizable in

this very life, Ditthadhamma Nibb§na V§da.

• •

The Buddha said that whatever samanas and brahmanas

speculated on the past, or the futur~ or both the

pa§t and the future, they did so in these sixty-two ways

or one of these sixty-two ways.

The Buddha announced further that he knew all

these wrong views and a lso what would be the destination,

the next existence, in which the one holding these views

would be reborn.

The Buddha gave a detailed analysis of these

wrong views a sserted in sixty-two ways p·nd pointed out

that these views had their origin in feeling which arose

as a result of repeated contact through the six sense

bases. Whatever person holds these vrrong views, in him

feeling gives rise to craving; cra'~ng gives rise to

clinging; clinging gives rise to existence; the kammic

causal process in existence gives rise to rebirth; and

rebirth gives rise to ageing, death, grief, lamentation,

pain, distress and. despair.

But whatever person knows, as they really are,

the origin of the six sense bases of contact, their

cessation, their pleasurableness, their danger and the

way of escape from the-m, he realizes the dhamrnas, no-t only mere morality, sila, but also concentration,samadhi,

and liberation, vimutti, wisdom, pann~, that transcend.

all these wrong views.

All the samanas and brahmanas holding the sixty-

two categorie::: of wrong views are' caught in the net of

this discourse just like all the fish in a lake are contained

in a finely meshed net spread by a skilful fisherman

or his apprentice.

(2) Samannaphala Sutta, Discourse on the Fruits of the

Life of a Samana

•

On one fullmoon night while the Buddha was

residing in R~jagaha at the mango grove of Jivaka this

niscourse on the fruits of the life of a samana, personally

experienced in this very life, was taught to

King Ajatasattu on request by him. The Buddha explained

to him the advantage of the life of a samana by

giving him the examples of a servant of his household

28

or a landholder cultivating the King's own land becoming

a samalJ8 to whom the King himself would show respect and

make offerings of requisites, providing him protection

and security at the same time.

The Buddha provided further elucidation on other

advantages, higher and better, of being a samana by elaborating

on (i) how a householder, hearing the'dhamma

taught by a Buddha, leaves the homelife and becomes a

samana out of pure faith; (ii) how he becomes establi- • shed in three categories of sila, minor, middle and

major; (iii) how he gains control over his sense-faculties

so that no depraved states of mind as covetousness

and dissatisfaction would overpower him; (iv) how he becomes

endowed with mindfulness and clear comprehension

and remains contented; (v) how, by dissociating himself

from five tindrances, he achieves the four jhanas

the first, the second, the third and the fourth as

higher advantages than those previously mentioned, (vi)

how he becomes equipped with eight kinds of higher knowledge,

namely, Insight Knowledge, the PO\'ler of Creation

by Mind, the Psychic Powers, the Divine Power of Hearin&

Knowledge of the Minds of others, Knowledge of Past Existences,

Divine Power of Sight, Knowledge of Extinction

of mral intoxicants.

Thus when the knowledge of liberation arises in

him, he knows he has lived the life of purity. There is

no other advantage of being a samatla, personally experienced,

more pleasing and higher than this.

(3) ~cbattha Sutta • • •

ArnbaHha, a young disciple of Pokkharasati, the

learned bra~n, was sent by his master to investigate

whether Gotama was a genuine Buddha endowed with thirty-

two personal characteristics of a great man. His insolent

behaviour, taking pride in his birth as a brahmin,

led the Buddha to subdue him by proving that Khattiya

is in fact superior to Brahr~~a. The Buddha explained

further that nobleness in man stemmed not from birth

but from perfection in three categories of morality,

achievements of four jhanas, and accomplishments in

eight kinds of higher knowledge.

(4) Sonadanda Sutta •

•

This discourse was given to the brahmin So~adanda

who approached the Buddha while he was residing near

lake Gaggara at eampa in the country of Ailga. He was

asked by the Buddha what attributes should one possess

to be acknowledged as a brahmin. SOQBdanda enumerated

high birth, learning in the Vedas, good personality.

morality and knowledge as essential qualities to be a

brahmin. When further questioned by the Buddha, he

said that the minimum qualifications were roorality and

Imowledge without which no one would be entitled to be

called a br~hmin. On his request, the Buddha explained

to him the meaning of the terms mrality and Imowledge,

which he confessed to be ignorant of, -namely, the three

categories of morality, achievements of four jhanas and

accomplishments in eight kinds of higher knowledge.

(5) Ku~adanta Sutta

On the eve of offering a great sacrificial

feast, the brahmin KutBdanta went to sec the Buddha for • advice on how best to conduct the sacrifice. Giving the

example of a former King Mahavijita, who also 1llc1de a

great sacrificial offering, the Buddha declared the

principle of consent by four parties from the provinces,

namely, noblemen, ministers, rich brahmins and householders;

the eight qualities to be possessed by the king

who would make the offerings; the four qualities of the

brahmin ro:ral ~dviser who would conduct the ceremonies

and the three attitudes of mind towards the sacrifices.

With all these conditions fulfilled, the feast offered

by the king was a great success, with no loss of life

of sacrificial animals, no hardship on the people, no

one impressed into service, every one co-operating in

the great feast willingly.

The brahmin Kutadant& then asked the Buddha if

• there was any sacrifice which could be made with less

trouble and exertion, yet producing more fruitful

result. The Buadha told him of the traditional practice

of offering the four requisites to bhi!:khus of high

IOOrality. Less troublesotw and more profitable again

was donating C'l monastery to the Order of Bhikkhus.Better

still were the following practices in a scerding order of

beneficial effects. (i) Going tQ the Buddha, the Dhamma,

aDd the sa~ for refuge; (ii) observance of the l'ive

Precepts; (iii) going forth from the hotwlife am leading

the holy life, becoming established in morality,

accomplished in the four jh~nas, and equipped with eight

okifndesxtoinfchtiiognheor fka-nsoawvleadsg, ethreesusaltcirnigficine wthheichreaelnitzaaitlison

less trouble and exertion but which excels all other

sacrifices.

(6) Mahali Sutta

Mahali Otthaddha, a LicchavI ruler, once came to

• • see the Buddhe to whom he recounted what Sunakkhatte, a

Licchavf prince, h~d told him. Sunakkhatta had been a

dleisfctipthlee oTfe.:tlhcheinBgu. dHdheatofoldr Mt.h... lrh-ea~liyeho~vrlsheefhteadr wachqicuhirehde

the Divine Povrer of Sight by which he had seen myriads

of pleasant, desirable forms belonging to the deva world

but that h-e had not heard sounds belonging to the deva world. l~h.:lli wanted to know from the Buddha whether Sun.

a khatta did not htClr the sounds of the deva world beca

se they were non-existent, or whether he did not hear

them although they existed.

The Buddha explained that there were sounds in

the deva world but Sunakkhatta did not hear them because

he had developed concentration only for one purpose, to

achieve the Divine Fower of Sight but not the Divine

Power of Hearing.

The' Buddha ~xplained furth~r that his disciples

practised the noble life under him not to acquire such

divine povJcrs but with a view to the re;:llization of

dhamrras which far excel and transcend these mund3ne kinds

of concentrntions. Such dhamrnas nre attainments of the

Four States o.f Noble Fruition 0 states of a stream-

owf inmnin0dr,an1doknnco~\-orlleetdugreneorf, ana Anornnh-aret tufrreneedr,oafnad ltlhe-asasvtaatse

that have been rendered extinct.

The Path by which these dhaa~s can be realized

is the Noble Path of Eight Constituents: Right, View,

Right Thought, Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood,

Right Effort, Right ~indfulness, Right Concentration.

.

(7) JallyaSutta

Once when the Buddha was residing nt Ghositnrarna

Monastery ne.:lr Kosarnbf, two wandering asc~tics

MU~9iya and Jaliya approached him and asked ~hether

31

the soul was the plvsical body, or the physical bod7

the soul, or whether the soul was one thing and the

physica1 body another.

The Buddha explained how a person who had

finally realized liberation would not even consider

whether the soul was the physical body, or the physical

body the soul or whether the soul was one thing and the

physica 1 body another.

(8) Mahasihanada Sutta

This discourse defines what Cl true samaI)tl is,

what a true brahmaI)B is. The Buddha was residing in the

aDseceer tPicarkKaossfapKaa•na•npapkraotahcahlaedahtimUraunndi'ias. aidThtehnatthehenhaakdedheard

that Samana Gotama disparaged all practices of self- • -oortification and that Samana Gotama reviled all those

who led an austere life.

The Buddha replied that they were slandering

him with what was not said, what was not true. When the

Buddha could see with his supernormal vision the bad

destinies as well as the good destinies of those who

practised extreme form of self-Jrortification, and of

those who practised less extreme forms of seli-roortification,

how could he revile all systems of self-mortification.

Kassapa then maintained thnt only those recluses

who for the whole of their life cultivated the practice

of standing or sitting, who were abstemious in

food, eating only once in two days, seven days, fifteen

days etc.~ were real samaqas and brallifu1~as. The Buddha

explained to him the futilit;r of extreme self-Jrortification

and said that on~ when a recl~se practised to

become accomplished in morality, concentration and

knowledge; cultivated loving-kindness, 8nd dwelt in the

emancipation of mind, and emancipation through knowledge

that he wculd be entitled to be called a samana

and brahmat;JB. Then the Buddha gave full exposition on

IOOrality, concentrat:ion a nd knowledge, resulting in

Kassapa1s decision to join the Order of the Buddha.

Potthapada Sutta • •

Once wheh the Buddha was staying at the

•

Monastery of AMthapiQQj.ka in the Jeta Grovf.: at 5avatthi

he visited the Ekas§laka Hall where various views

were debated. At that time POt.t.hB~da the wandering

ascetic asked him about the nature of the cessation of

Consciousness (saNia). P01t\hapada wanted to know how

the cessation of Consciousness was brought about. The

Buddha told him that it was through reason and cause

that forms of Consciousness in a being arose and ceased.

A certain fore of Consciousness Brose through practice

(Adhicitta si~) and a certDin form of Consciousness

ceased through practice.

The Buddha then proceeded to expound on these

practices consisting of observance of slla and development

of concentration which resulted in arising and

ceasing of successive jh~nas. The meditator progressed

from one stage to the next in sequenc0 until he achieved

the Cessation of all forms of Consciousness (nirodha sam!

patti) •

(10) Subha Sutta

by his cTlohsies aistteanddaisncto, utrhsee gV~ivneenranbloct Ab-ynatnhdea,Bounddhthaebut

request of young Subha. The Buddha had passed ~way by

then. And young Subha ~nted to know from the lips of

the Buddha's close attendant what dha~s were praised

by the Buddha and whut those dhall1lM s were which he urged

people to practise.

Ananda told him that the Buddha had words of

praise for the three aggregates of dhamma, namely, the

aggregate of morality, the aggregate of concentration

and the aggregate of knowledge. The Buddha urged people

to practise these dh-a~s, dwell in them, and h~v~ them firmly established. Ananda explained these aggregates

of dhamrno in great det~il to young Subha, in consequence

of which he became a devoted lay disciple.

(11) Kevatta Sutta ~

••

~

The Buddha was residing at mlanda in p~van.hC' ~.

•

ma~ grove. A devoted lay disciple approached tilt:: f·t;cdha

a.m urged him to let one of his disciples perfc,rLi , miracles so that the City of N5+and~ would beco~ tlVH

80 much devoted to the Buddha.

33

The Buddha told him sbout the three k:i.D1e of

miracles which he had known and realized. by himself

throlJgh 8upernormal knowledge. The first miracle, iddh1

riya, was rejeoted by the Buddha because it could

be mistaken as the black art called GandMr1. magic. The

Buddha also rejected the second miracle, AdesaCfnStih'AriB,.

which might be mistaken as p%'actice of nU~n1

charm. He recommended the pertormnce of the third mi~

racla, the anuS§aaN P!t~~ the miracle of the

power of the Teaching a("'it involved practice in Morality,

Concentration and Knowledge leading finally to the

Extinet10n of Asav8L Asavakkhaye mlna •

•

(12) Lohicca Sutta

The discourse lays down three t.ypes of blameworthy

teachers: (i) The teacher who is rot yet accourplished.

in the noble practice and teaches pupils who d~

not listen to him. (ii) The teacher who is not yet accomplished

in the noble practice and teaches pu:,ils wh.)

practise as instructed by him and attain emancipation.

(iii) The,,~teacher who is fully accol!Iplished in ....he noble

practice' and te~'cnes pupils who do not listen to him•.

,The praiseworthy 'teacher is one whH'has become

fully ~ccomplished in the three practices of Morality

Concentration and Knowledge and tea ches pupils \fflO bt:come

fully accomplished like tim.

( 13) .Tevij ja Sutta

- ..

Two brahmin youths V~settha and B~radv~j8 ca~

to see the Buddha while he was on ., tour thrcugt:l tliEo

Kingdom of Kosala. They wanted thE:: '3uddr.a to s~t.tle

their dispute as to the correct path that led stl'81.ght

to companionship with the Brahm8. Each one thought

only the way shown by his own master was the true one.

The Buddha told them that as none of their

masters had seen the Brah~, they were like", line of

blind men each holding on to the preceding one. Th~n

he showed them the true path that really led to the

Brahm3 realm, namely, the path of mrality arod concentration,

and development of 10ving-kindness,C0mp86sion,

sympathetic joy and equanioity toward~ all sentient

beings •

GT, F.)

34

(b) MahB Vagga -Pall

•

The Large Division

The ten suttas in this elivision are some of the

most important ones of the Tipitaka, dealing with historical,

and biographical aspects as well as the doctrinal

aspects of Buddhism. The most famous sutta is the

MahSparinibbtma Sutta which gives an account of the last

days and the passing away of the Buddha and the distribution

of his relics. Mahapad~na Sutta deals with brief

accounts of the last seVQn Buddhas and the life story of

the vipassI Buddha. Doctrin~lly important arb the two

suttas: the Mahnnid~na Sutta which explains the Chain of

Cause and Effect, And the Ivlahasntipat.1;-hana Sutta dealing

with the four Methods of Steadfast jv1.indfulness and practical

aspects of Buddhist meditntion.

(1) loBMpad~na Sutta

This discourse waG given at S~vatthi to the

bhikkhus who were one day discussing the Buddha's knowledge

of past existences. He told them about the last

seven Buddhas, with a full life story of one of them,

the Vipassi Buddha, recalling all the facts of the Buddhas,

their social rank, name, clan, life-span, the

pairs of Chief Disciples, the assemblies of their followers,

their attainments, and emancipati~n from defilements.

The Buddha explained that his ability to remember

and recall all the facts of past existences was due

to his own penetrating discer~ent as well as due to

thE devas making these matters known to him.

(2) Mahanid'llna Sutta

This discourse was given at Ka~sadhamrra market

town to the Venerable Ananda to correct his wrong

view that the doctrine of Pa~iccasamuppada, although

having signs of being deep and profound, was apparent

and fathomable. The Buddha told him that this doctrine

not only appeared to be deep and profound but was actually

deep and profound on four counts: it was deep

in meaning, deep as a doctrir.e, deep vnth respect to

the manner in which it was taught, and deep with regard

to the facts en which it was established.

~e then gave a thorough exposition on the

35

doctrine and said that because of lack of proper understanding

and penetrative comprehension of this doctrine,

beings were caught in and urtsble to escape trom, the

miserable, ruinous round of rebirth. He concluded that

without a clear understanding of this doctrine, even the

mind of those, accomplished in the attainments of jhana,

would be beclouded with ideas of atta.

(3) Mahaparinibbana Sutta

This sutta is an important narrative of the

Buddha's last days, a detailed chronicle of what he did,

what he said and what happened to him during the last

year of his life. Compiled in a narrative form, it is

interspersed \'lith many discourses on SOIll:l of the most

fundamental and important aspects of the Buddha's Teaching.

Being the longest discourse of the Digha NikaY3, it

~s divided into six chapters.

On the eve of the last great tour, the Buddha

while staying at Rajagaha gave the famous discourses on

seven factors of Non-decline of kings and princes and

seven factors of Non-decline of th~ hhikkhus.

Then he set out on his last journey [cing first

to the village of Patali where he taught on the ccnse- • quences of an i.mrr.oral and a mora 1 life. He theu proceede1

to the village of Koti where he (.xpounded. on the Four

• Noble Truths. Then the Buddha took up his re~idence at

the village of Natika where th8 famous discourse en thE'

Mirror of Truth was given.

Next the Buddha \/Hot to Vesali \\1.th a large conppany

of bhikkhus. J\t VesiiH be a cCE::pted the p.:'irk offered

by the Courtesan AJr.bapali. l-rorn Vesili, th8 Buddha tra-

• veIled to a small viJ.l<!L~t:: nar.:·.::d V~luva where he 'rJS Clv€'r-

• taken by a severe illness that could !:;j ve prc·ved fata 1.

But the L~ud.dha resolvL,d to mainf.,<liu the life-proces:') and

not to p.7lSS away without addre$~ing his by disciples

and withcut t.~lci.ng ll.:.we of the 3:lIi,glla. /her' AIIt!w1a it~formed

tht: j~l.lddha how \-lorried h:' : '1d b';.:-.n 'Jeeau:;o''; of tne

Buddha I s illness, the 3uddh:l go v~ tt, famol]s inj lm(~t.ioh:

"Let yvu:r:;~lvcF; 1)l; YO'Jr owr S\lppc,rt" Y~)\U' ow!' t·~fUbt·.; ...

Let t.he: Jh?n1l".J3, not.. allythirl{ else, :•.. your n: rut', ." lul

It was ct Vesali that the Buddha made the decision

to pass away and reali:.;E' p~rin.i.i:bana in thr,:e ,gq

IOOnths' time. Upon his making this l~mcntous decision~ 'Ja

36

- there was a great earttquake. Anama, on learning fr'om

the Buddha the reason of the earttquake, supplicated him

to change the decision, but to no avail.

The Buddha then caused the Samgha to be 8SSeIlPo

bled to whom he announced his approaching parinibblna.

He then went over all the fundamental principles of his

Teaching and exhorted them to be vigilant, alert, and

to watch over one's own mind so as to make an end of

suffering.

The Buddha then left Vesali and went to Bhanda

Village where he continued to give his dis~ourses to •the

accompanying Sadlgha on sila, saddhi and pannA. Proceeding

further on his journey to the north, he gave the

discourse on the four great Authorities, Hahapadesl, at

the town of Bhoga.

From there he went on to P~v~ and stayed in

the XamgoGrove of CunQa, the Goldsmith's son, who made

an offering of food to the Buddha aoo his comnunity of

bhikkhu.. After eating the meal offered by Cunda, a

severe illness came upon the Buddha who nevertheless

continued on his journey till he reached KusinAr-;§ where in the sal Grove of the Malia princes he urged Anarna

to layout the couch for him. He lay down on the couch